He had not anticipated his e-book to be so successful. It had been acclaimed not solely in Britain but in addition in America, the place he had by no means dreamed of going. All Ronald Blythe had considered, as he sploshed by the muddy fields of east Suffolk and the ditches working with yellow winter water, was the deep obscurity of the lives of rural labourers. That they had dug these ditches and laid these hedges, twisting the reluctant twigs of elder and willow. Now the hedges had grown unruly, regardless of their efforts. That they had ploughed their identification, their “I’m”, into the flat, clayey fields, and had then gone underneath that clay. Their names had been carved on headstones, however the Suffolk wind, which cared for nobody, had weathered them away. Maybe he, as a author, might nonetheless report the voices of nation people nonetheless dwelling.

Your browser doesn’t help the

The e-book he researched and wrote in 1967-68 was referred to as “Akenfield”. It was a group of flippantly anonymised monologues gathered from villagers within the space, primarily Charsfield, however going wider. Slowly, he penetrated their “bony quiet” to listen to Davie, an historical, remembering gangs of males singing as they scythed the corn; the blacksmith who couldn’t open a church door with out its hinges; the thatcher who introduced that hazel, to which he tied his reed bundles, was the most effective splitting wooden there was. The gravedigger informed jokes, as gravediggers will, and reminded him that our bodies should be buried dealing with east, anticipating their resurrection—aside from parsons, who should face the opposite method.

But comfy custom sat cheek-by-jowl with wrestle. A younger schoolmaster informed him how he had come to Suffolk to color its large skies, like John Constable, however now discovered himself instructing a reasonably gradual lot of pupils. The native Justice of the Peace talked matter-of-factly of the incest within the district, which might appear to each events a very pure incidence. A visiting nurse disabused him of cottager kindness by relating how the outdated had been usually stored in darkish corners, even in cabinets, and the way those that couldn’t produce their very own meals typically merely starved. A younger shepherd who firmly acknowledged that he “belonged to Suffolk” additionally thought from time to time of Australia, and the way good it might be to personal one thing, quite than taking care of the flocks of different males.

The trendy world was seen with ambivalence. The telly was good, vehicles had been handy, however the brand new commuter households spilling out of Ipswich had been judged to be taking part in at village life. Change was not unwelcome, however occurring too quick. To this view, Mr Blythe was gently sympathetic. If he had included a author in “Akenfield”—in addition to the poet, lurking close to the tip of the e-book, who stated he wouldn’t have come to reside there if he had needed to get on—it ought to have been himself.

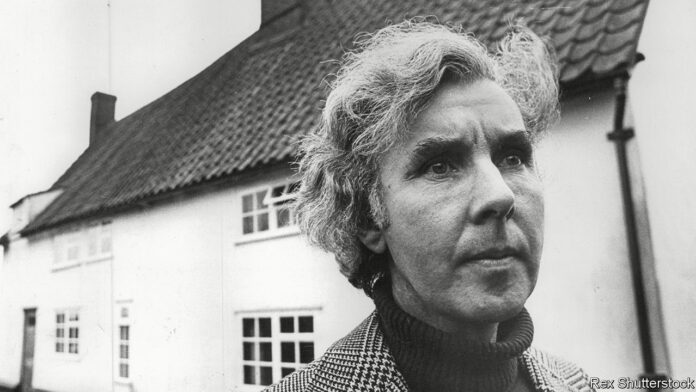

He had been born close to Lavenham, and had stayed in Suffolk, or on its Essex border, all his life. In reality, aside from one stint in Aldeburgh, writing programmes for Benjamin Britten, he had by no means stirred from the valley of the Stour. His father’s household had been farm labourers there, and agriculture was in his blood. He by no means noticed the purpose of transferring, or working at any uncongenial job, if he might make a dwelling as he favored. As a boy he would escape outdoors if any chores threatened, to discover the lanes on his bike or lie dreaming within the grass, watching clouds. College ended at 14. Progressively, with the encouragement of the artist-and-writer associates he met in his first, shy-librarian job in Colchester, his longing to be a author grew. Henceforward, he lived for phrases.

In that vocation he selected to be alone. Solitude, although damaged by expensive guests and his imperious cats, was good for writers. Alone, he might prepare his eye and ear to notice the glitter of flint, the “starry, branchy, excellent form” of widespread cow parsley, the scrape of the outdated willow at his window. He spent his final 4 many years in a really outdated home that had been left to him by the painter John Nash, Bottengoms Farm, on the finish of a mile of unmade observe that grew to become, with sufficient rain, a river. There he was provident, impartial and blissful. Within the raftered rooms he hung photos, within the backyard he planted potatoes and runner beans. The freezer held his harvests, with fussy labels of expiry dates. From ten til one he wrote, in a foolscap e-book with low-cost ballpoints, his books, essays, quick tales and, for 25 years, his weekly column for the Church Instances. 4 hundred phrases for the again web page. It happy him to be learn by bishops. After work, and lunch, he wandered. “We tried to get you,” the phone would inform him, plaintively, on his return.

On such perambulations, although, he was seldom actually alone. His thoughts swarmed with these, each small and nice, who had walked East Anglia’s fields and lanes earlier than him. He noticed Constable, along with his painty fingers, opening the door of Stoke-by-Nayland church, the place daylight might flip the tower from pink to gold to gossamer. He watched John Clare, better of all nature poets, skiving on a Sunday, mendacity within the ling to scribble on his hat. Simply as vividly he caught St Cedd, preacher to the East Saxons, standing underneath a dripping oak, and medieval villagers taking his personal paths, talking Chaucer and getting attractive in Maytime, underneath the hedges the place the speckled flowers gave off their erotic scent.

Chief amongst his heroes had been the three nice priest-writers of Anglicanism, George Herbert, Thomas Traherne and Francis Kilvert. That they had lived elsewhere, Herbert within the Midlands, Kilvert in mid-Wales, Traherne in Herefordshire. However as a lay reader himself spherical a cluster of thinly attended little church buildings, he crammed his sermons with these figures and trod of their methods. His head hummed with hymns and chants through which hills danced and bushes rejoiced earlier than the Lord. Church festivals marked the rhythms of his days: Passiontide and Easter, Good Shepherd Sunday, Rogation Day tramping the parish boundaries. Like his heroes, he made his native scene sacred. In his writings he celebrated them, Traherne the wonderful earth-enjoyer, Herbert regularly astonished on the generosity of his Lord. And Kilvert, the intrepid walker, revelling within the gentle, noting every part and everyone “with a sort of bliss”, listening so patiently to the tales of atypical nation people that they too had been transfigured. ■

Correction (February fifteenth 2023): The unique model of this story stated that Mr Blythe stayed in Suffolk all his life. In reality, Bottengoms Farm was simply on the Essex aspect of the River Stour.

This text appeared within the Obituary part of the print version underneath the headline “Sacredness in Suffolk”

From the January twenty eighth 2023 version

Uncover tales from this part and extra within the checklist of contents